HHS Secretary Alex Azar Touts White House Efforts to Fight Sickle Cell Disease

Written by |

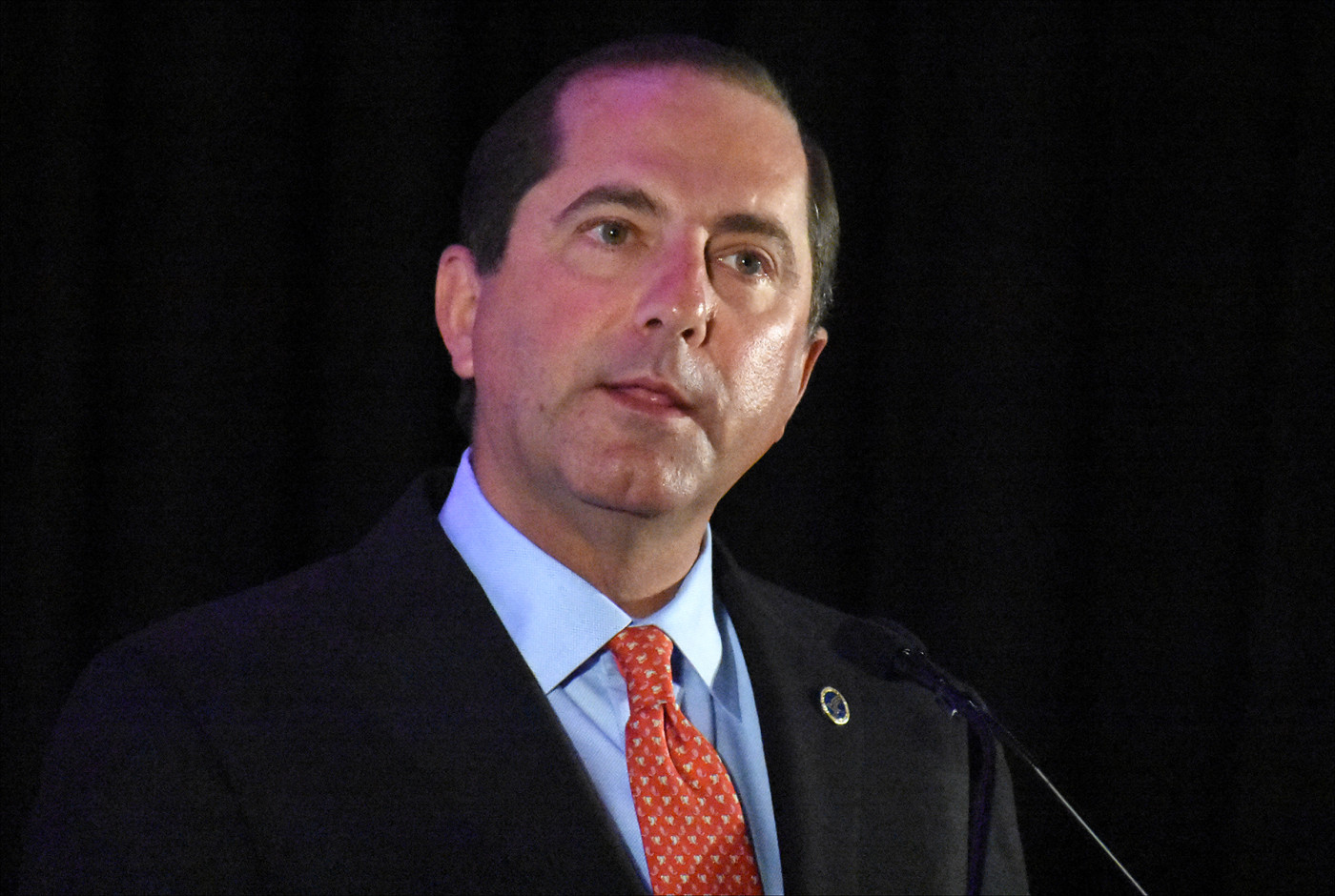

Alex Azar, U.S. secretary of Health & Human Services, addresses the NORD Summit in Washington. (Photo by Larry Luxner)

By 2029, Americans with sickle cell disease (SCD) could be living 10 years longer than they do today, predicts U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar.

That’s one of the Trump administration’s long-term goals, Azar — the nation’s top health official — told more than 900 delegates attending the 2019 NORD Rare Diseases & Orphan Products Breakthrough Summit in Washington, D.C.

The recent summit, organized by the National Organization for Rare Disorders, also featured speeches by Norman E. “Ned” Sharpless, MD, acting commissioner of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and his predecessor, former FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD.

In his 17-minute speech, Azar used SCD as an example of President Trump’s commitment to those with rare diseases.

“We believe we can make a meaningful impact quite soon on this terrible disease,” he said, noting that the illness affects about 100,000 Americans — particularly blacks and Hispanics — and causes excruciating pain as well as infections, lung damage, blindness, depression, and heart and kidney failure.

“While sickle cell disease has been neglected for far too long, today there are many, many reasons for hope,” Azar said. “In fact, it is one of the single most promising areas for biomedical research, and the Trump administration has made the disease a top priority. At HHS, we’ve set a goal of extending the lives of Americans with sickle cell disease by 10 years within 10 years.”

To that end, Trump late last year signed into law a bipartisan bill that reauthorizes a current SCD prevention and treatment program with funding of nearly $5 million each year over the next five years. The Sickle Cell Disease and Other Heritable Blood Disorders Research, Surveillance, Prevention, and Treatment Act of 2018 had been co-sponsored by Sens. Cory Booker (D-New Jersey) and Tim Scott (R-South Carolina).

A ‘global health challenge’

Among other goals, Azar said HHS is looking at how to address the challenges sickle cell patients face when transitioning from pediatric to adult care, as well as expanding data collection efforts by the Atlanta-based Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

“Sickle cell is also a global health challenge, and more than 300,000 babies are born with it in sub-Saharan Africa every year; 50% to 80% of them will die by the age of 5,” Azar said.

“A value-based approach to care delivery means greater collaboration between doctors, researchers and patients, especially in underserved areas or areas with few SCD patients,” he said. “Today, only one in four patients with sickle cell disease receives standard of care.”

Azar, who assumed leadership of HHS in January 2018 following his Senate confirmation, served as president of the U.S. division of Eli Lilly & Company from 2012 to 2017. He noted that 40 therapies to help manage SCD-related pain are currently being tested in clinical trials.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) announced in October that it plans to invest at least $100 million over the next four years toward developing affordable gene-based cures for both SCD and HIV. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation also will put $100 million toward this goal.

“The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [NHLBI, a division of NIH] now believes a cure is within our reach in the next 5-10 years,” Azar said. “In Boston, I met a young man whose blood is now sickle-free as a result of the gene therapy he received through a clinical trial. This is an incredible triumph of modern medicine, and you should all be proud.”

Yet that’s only part of the challenge, Azar said. Paying for all these new treatments could be even a bigger battle — especially considering the $2.1 million price tag for the recently approved one-time AveXis gene therapy Zolgensma for spinal muscular atrophy.

“Gene therapies have typically carried unprecedented high prices, and the same will likely be true for a cure for sickle cell. Progress must prompt us to think about how we’re going to finance the delivery of these cures,” he said.

“The cures are coming — thank God they are — but when they arrive, we’ve got to be ready to get them to patients who desperately need them,” Azar added. “All of the actors involved — HHS, private payers, innovators, legislators and patient advocates — need to be thinking now about how to build a system together that can support access to these cures. The whole point of a health insurance system like we have is to ensure that if you are struck by a serious illness — let alone one that is rare and highly unlikely — our system is there to care for you.”

Patient groups welcome speech

Debrilya Williams, a social worker with the Sickle Cell Association of Texas, said she was pleasantly surprised with Azar’s presentation.

“I wasn’t expecting to talk about sickle cell, because a lot of people really don’t know about this disease,” said Williams, whose nonprofit has offices in Austin, San Antonio, and Houston. “It was well-stated and beautiful to know that sickle cell is starting to get the recognition that is needed, so we can go forward and find a cure for this disease.”

Lakiea Bailey, PhD, is executive director of the Georgia-based Sickle Cell Community Consortium, a four-year-old nonprofit that partners with community-based organizations as well as independent patients and caregivers in 23 states and Canada.

“It’s been made clear by HHS that sickle cell is a priority,” said Bailey, largely crediting Admiral Brett P. Giroir, MD, the assistant secretary of health, for this new effort. “He’s a physician and was greatly impacted by sickle cell. So he’s made it a priority to ensure that sickle cell is no longer on the sidelines. So has the former president of the American Society of Hematology, Dr. Alexis Thompson, as well as the NHLBI. You have groups like this all saying sickle cell now matters.”

Bailey, who has a doctorate in molecular hematology and regenerative medicine, suggested that the sudden interest in sickle-cell research coincides with the U.S. opioid epidemic — which has hit black Americans particularly hard — as well as recent progress in cell and gene therapy.

“Sickle cell has been at the center of multiple scientific breakthroughs and is the perfect model disease to study — a disease whose molecular basis is completely understood,” Bailey said. “We know exactly what goes wrong in the gene, down to the specific amino acid mutation. And knowing its molecular basis allows you to study it on a level that other diseases aren’t afforded.”